This is about approaching extension as a bottom-up process to achieve change – as an exercise in human development for outcomes that have an impact at the farm, community and industry scale (Coutts et al., 2005). It uses a facilitation process to help groups of motivated participants to identify and understand their own learning needs and to assist them in fulfilling these needs.

An extension practitioner becomes the facilitator providing the enabling environment for self-directed and social learning to take place amongst individuals and communities who take the initiative to define and respond to problems from their perspectives.

The assumption is that the opportunity for individuals and communities to interact on a commonly understood problem or situation as a process of self-determination, will and can bring about an improvement to the situation.

The strengths of developing extension projects under this model include:

- It accommodates multiple perspectives and collaborative working relationships when addressing complex issues

- It provides a means of stimulating, motivating and organising people to seek resources as needed

- It can involve a diversity of people in problem solving at the ground level, which is an opportunity that is not readily provided at the institutional level

The following is a check list to assist in the identification and development of a Group Facilitation/Empowerment model of extension:

- Do the potential participants (project team or individuals) express or endorse a need for facilitation assistance?

- Are the groups are self-selected?

- Are the facilitators selected or endorsed by the group participants?

- Is a planning cycle incorporated into the process, including reflection on progress?

- Do group members have the opportunity to receive training in group processes and planning?

- Do groups meet regularly and share experiences?

- Are boundaries for use of funder resources and reporting needs negotiated and agreed to by funders, the project team and group members?

- Are opportunities made for professional development of facilitators and to develop facilitator networks?

- Are group members encouraged to benchmark their knowledge, attitudes and practices to assist in learning about the impact of the Group Facilitation/Empowerment project-process?

- Do group members contribute an increasing level of their own resources to group activities

- Are courses and workshop opportunities made available as part of the learning opportunities, that then become incentives to be involved in the project-process

Content Source

Coutts, J., Roberts, K,. Frost, F., and Coutts, A. (2005). The role of extension in building capacity: What works and why. Barton, A.C.T., Rural Industries and Development Corporation: Cooperative Venture for Capacity Building

Key Example 1: Towards Whole of Community Engagement: A practical toolkit

This example is relevant to an agricultural extension context of group extension and/or empowering the farmer in decision-making within the advisor-client relationship. The approach was developed as part of a project commissioned by the Murray-Darling Basin Commission (MDBC) in a natural resource management context at a regional/community scale.

Best practice in community engagement advocates for participatory approaches that include a full range of stakeholders and their knowledge systems in order to have a real ability to shape and implement change as a bottom-up approach. This is because top-down processes in which authorities/experts adopt a directive role have typically not succeeded in bringing about community-scale change.

The project objectives were to: develop principles of best practice in engagement processes, describe the range of communication methods and processes that can be used, identify impediments to the adoption of best practice engagement processes and develop performance indicators for uptake and use of best practice engagement.

Key Definitions

- Stakeholder: Is anyone who has an interest in an issue (financial, moral, legal, personal, community-based, direct or indirect)

- Community: Is usually regarded as a group of people living in a specific area; but can also mean a ‘community of interest’ where members may not live geographically near each other but share a common interest in an issue/cause in which they can develop collective responses.

- Community engagement: Refers to engagement processes and practices in which a wide range of people work together to achieve a shared goal guided by a commitment to a common set of values, principles and criteria i.e. an engagement structure. Community engagement can be achieved using a diverse range of techniques and tools to suit the particular situation; the engagement process supports the decision-making process needed to problem solve for a particular purpose.

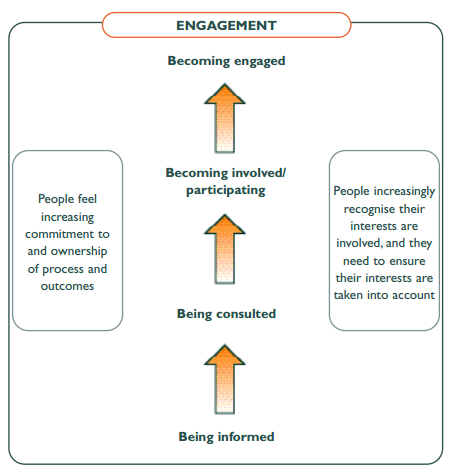

Consultation, participation, involvement: A distinction is made between consultation, participation, involvement and engagement to highlight that engagement implies the greatest commitment to the process, decisions made and resulting actions. Engagement goes further than participation and involvement and requires greater focus, time and effort. In contrast, consultation is about seeking advice from others; participation is simply the act of participating in any form and involvement is the act or process of being involved.

Engagement: Aslin, H.J. and Brown, V.A. (2004) Towards whole of community engagement: a practical toolkit, MDBC: Canberra, p. 5

- Development of good community engagement processes is based on a set of principles:

- Mediate for change: Accept engagement is not to maintain status quo or accept the lowest denominator, but to make a difference in the right direction

- Agree on values: Being transparent about what is valued around engagement and change and generate support for some key values

- Effective communication: Engage a wide group of people and be clear in how messages are communicated

- Develop and commit to a shared vision: Establish common ground in the form of a shared vision to galvanise action towards an agreed goal

- Representativeness: Engage those to represent a wider constituency, not just those views that align with your own, make sure any ‘interest group representatives’ also seek their views within their group and are not just representing their own

- Mutual learning: Accept that no-one has all the answers and everyone has something to learn and contribute

- Working towards long-term goals: Accept that it make take some time to achieve goals and that it can be a slow process

- Base processes on negotiation, cooperation and collaboration: Be prepared to approach community engagement with an open mind, without prescribed ideas and be motivated to negotiate with other towards mutually agreeable solutions

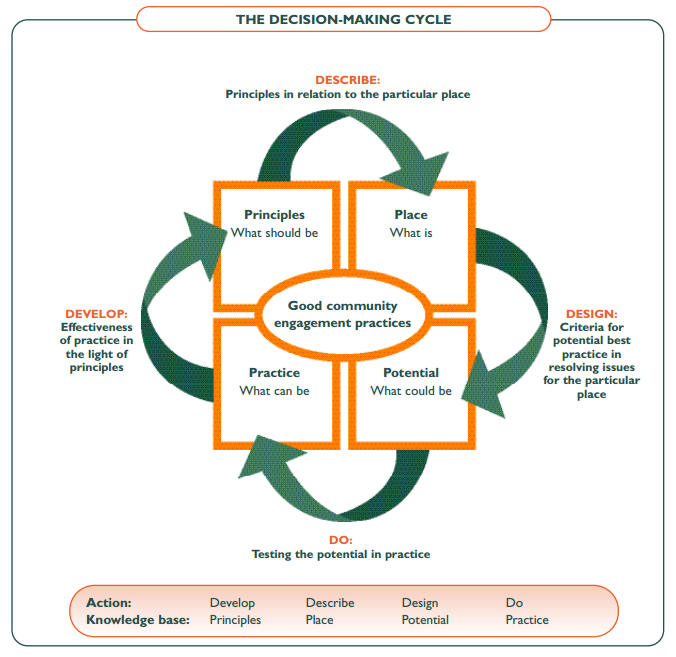

The decision-making cycle

Inquiries and problem solving in the community engagement process are understood and framed using Kolb’s experiential learning principles (Kolb et al., 1974; Kolb, 1984): the four steps of the experiential learning cycle and their equivalent stage of the decision-making cycle are – 1) Concrete experience (describing), 2) Observation and reflection (designing), 3) Active experimentation (doing) and 4) Abstract conceptualisation (developing)

The decision-making cycle: Aslin, H.J. and Brown, V.A. (2004) Towards whole of community engagement: a practical toolkit, MDBC: Canberra, p. 11

Unless the decision-making cycle as part of action research in a learning system is fully completed, experiential learning does not fully occur and the inquiry is incomplete. In reference to applying this approach to the community engagement process, the same principle applies i.e. unless communities and individuals are engaged right around the decision-making cycle, their opportunities to contribute to outcomes and undergo learning experiences are not realised effectively.

Diverse knowledge bases and cultures

The authors acknowledge that different knowledges and cultures exist when bringing together multiple stakeholders (individuals/groups) but each knowledge base has something to contribute to the engagement and decision making process. The value of the different knowledge bases are to provide the context to the situation, define the process principles, scope the potential of what could be and to shape what actions can take place in real-world situations. Linking this with the decision making cycle, the knowledge bases become inputs across the decision making cycle, (describe, design, do and decide). These knowledges are identified as follows:

- Local knowledge: The local reality based on lived experience in the region, built through shared stories, memories of shared events and locally specific relationships between people and places (CONTEXT-PLACE)

- Specialised knowledge: The collected advice from a wide range of experts from academia, government, private sector, public sector etc., each constructed within a particular knowledge framework or paradigm (POTENTIAL)

- Strategic knowledge: The tactical positioning of people and resources for future action within given political and administrative systems (PRACTICE)

- Integrative knowledge: The mutual acceptance of an overarching framework, direction or purpose, derived from a shared interpretation of the issues (PRINCIPLES)

It is important to note that participants in engagement processes need to constantly adjust and compensate for people belonging to particular knowledge systems/bases that tend to often reject other knowledge traditions/bases. People may dismiss local knowledge as ‘gossip’, specialist knowledge as ‘jargon’, strategic knowledge as a pre-set ‘done deal’ and integrative knowledge as ‘impractical’. The idea is to give equal respect to each knowledge base/system.

A Tool Inventory for the Five Decision Making Cycle Categories

Generic tools (that can be applied at any stage of the decision-making cycle)

- Generic public involvement and participation

- Negotiation and conflict resolution

- Information, education and extension

Descriptive tools

- Rapid and Participatory Rural Appraisal

- Stakeholder analysis and social profiling

- Survey and interview

Designing tools

- Planning and visioning

- Team building and leadership

Doing tools

- Participatory Action Research

- Deliberative democracy

Developing tools

- Lobbying and campaigning

- Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation

Indicators of Success in Community Engagement per Social Group

Successful community engagement is viewed differently depending on the purpose and the community or groups involved. Some examples of the diversity of indicators of successful community engagement include:

- For a local community members: improved project outcomes

- For specialist advisers: validity, accuracy, and reliability of information

- For government agencies: degree of clarification of project aims and objective

Impediments to successful community engagement per social group:

- For local community members: No history/experience of formal negotiations to draw upon

- For specialist advisers: Gaps between different knowledge systems and perspectives

- For government agencies: People not taking responsibility for the collective decision made

- For coordinators: Lack of long-term, stable and continuing communication channels

Key Example 1: Content sources and further information

Aslin, H.J. and Brown, V.A. (2004) A framework and toolkit to work towards whole-of-community engagement.

Key Example 2: Evaluation Empowerment

Many rural development projects aim to increase the empowerment of project stakeholders as part of capacity building but seldom is there a process or tools to benchmark and measure the impacts of this dimension of capacity building. The following is a guide (process and tools) aimed at capacity building practitioners, funders and evaluators to help them to be able to know how to build empowerment and measure and assess any related changes as capacity building indicators.

It is based on the assumption that people could be taken through processes to develop their individual and collective capacity to learn better, make better decisions and become more self-sufficient with regards to their learning. It draws on a range of principles from the education, instructional design and management literature regarding empowerment. This project was funded through the Cooperative Venture for Capacity Building in Rural Industries. To download the details on the initiative click on the image below.

Key definitions

- Empowerment: People having the skills and confidence to proactively respond to issues and make the most of the opportunities available to them.

- Capacity Building: Externally or internally initiated processes designed to help individuals and groups associated with rural Australia to appreciate and manage their changing circumstances, with the objective of improving the stock of human, social, financial, physical and natural capital in an ethically defensible way.

Key Findings from this Project

- Six skills can be associated with empowerment that are most relevant to extension practice:

- Critical thinking – is demonstrating qualities of good thinking processes concerned with analysis, evaluation and problem solving; critical thinkers demonstrate this skill by being habitually inquisitive, engaging with problems and making decisions, caring that beliefs and positions are represented truthfully and that decisions are justified and caring about the dignity and worth of every person; critical thinkers have the ability to clarify, judge, infer, make suppositions and use auxiliary critical thinking abilities;

- Planning – knowing how to plan, reasons for planning (i.e. different purposes: strategic, management, operational and communication) and the target audience are all key components of planning; knowledge about program logic or theories of change is also a key component of knowing how to plan; good planning foreshadows the possibility that the plan itself may need reviewing so a process will need to be developed for this double-loop learning;

- Communication – higher level communication is not just about communicating a message to a receiver, it is also about having the ability to resolve conflicts and negotiate win-win outcomes as part of managing the impact of communications; higher level communication relies on the messenger knowing about oneself (social intelligence that is developed from learned behaviour/emotional intelligence) which enables a person to understand other people’s thoughts, feelings and intentions, possess extensive knowledge of rules and norms in human relations, can empathize and manage their own and others emotions, adapts well to social situations and is open to new experiences, ideas and values. The relevant skill-set for communication is: The ability to communicate, listening skills, the ability to create a message, conflict management, negotiation, advocacy, be motivational and well developed self-knowledge.

- Facilitation – is about helping groups of people interact with each other more effectively across a wide range of situations, facilitation skills are closely linked with communication skills (social intelligence); it requires an attitude of guiding rather than leading; it is about developing a dynamic of assisting and supporting rather than taking control; indicators of facilitation capacity are associated with knowing what to do and having a particular mind-set

- Community cooperation/social networks – networks connect individuals with each other at the individual and organisational level, the value of social networks can be measured in economic terms e.g. saving costs by sharing resources, the extent of ‘reach’ and diversity (the depth and breadth of a network), the contribution and implementation of innovative ideas, and the cultural change that may come from being connected to a network; a network can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively using Social Network Analysis methods.

- Leadership – refers to an individual’s ability to influence, inspire, motivate, guide and direct others to achieve a common or shared goal; leadership is enhanced by the individual ‘leading by example’ and when they can empower others to act; leaders have vision, can communicate, are confident, make good decisions, empathetic and above all else, are respected; it is recognised that there are two types of leaders: those who shape an direct and those who coordinate.

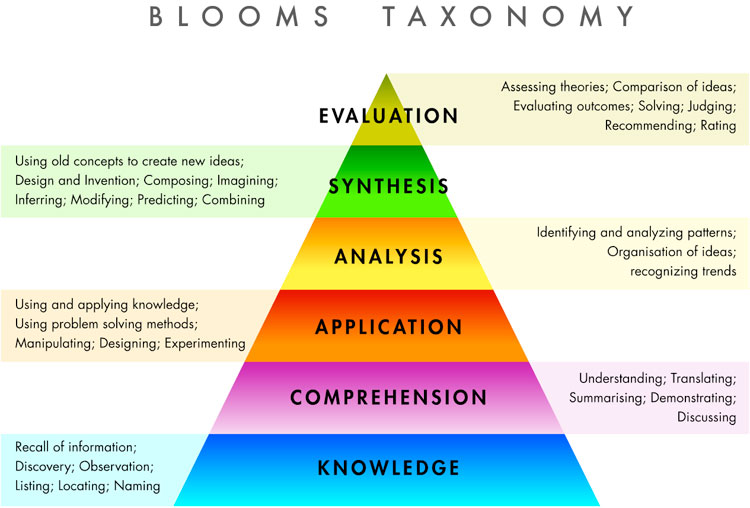

The presence and comprehension of these skills alone does not indicate whether empowerment is being developed and exercised, rather it is the level of mastery at which the skills are used that is the real evidence i.e. it is the ability to synthesize (modify and apply appropriately to specific situations) and evaluate the use of these skills that brings about empowerment.

Once these skills are well developed a person can be considered as having the attributes of empowerment which are closely related to the characteristics of self-efficacy (e.g. faith in own capabilities, knowledge of self, commitment to truth, ability to work collaboratively and communicate openly, respect for others and the capacity to make choices and to transform those choices into desired actions and outcomes).

The extent to which an individual is empowered varies with the particular context and not all skills are needed for an individual to be empowered. Becoming empowered is a process of skills development by firstly understanding what your current skill set is, choosing which skills need developing in the given context, the acquisition of skills through a learning process and being capable of demonstrating those skills as an indication of empowerment.

Not everyone can be empowered in all situations but an individual can choose which situation they want to be empowered in and develop the skills needed to achieve that. Referring to Bloom’s hierarchy of learning, the level of skill needed for empowerment is at the higher end of the continuum beyond the level of analyses and application and moves into the learning space of synthesizing and evaluating. This is because empowerment requires the individual to be able to self-assess/self-reflect about their modified application of themselves in a certain situation as a demonstration of a person’s empowerment i.e. owning and evaluating your own experience is an act of empowerment in itself.

Blooms hierarchy of learning: Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn & Bacon

Key Example 2: Content sources and further Information

Roberts, K.. & Coutts, J. A., & the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (Australia) (2007). Evaluating empowerment: The human element of capacity building : a report for the Cooperative Venture for Capacity Building in Rural Industries. Barton, A.C.T.: Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation pdf available here

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn & Bacon