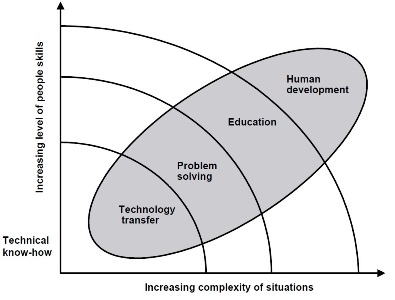

The extension continuum recognises that there are four major strategies or models in agricultural extension. It illustrates that as extension situations become more complex, emphasis should be given to approaches, processes and tools that empower people to engage in ongoing processes of experimentation, learning and human development.

It recognises that there are four major strategies or models in agricultural extension:

1. Linear ‘top-down’ transfer of technology

2. Problem solving (one-to-one advice or information exchange)

3. Education (formal or structured)

4. Participatory ‘bottom-up’ participatory approaches – human development

It illustrates that as extension situations become more complex, emphasis should be given to approaches, processes and tools that empower people to engage in ongoing processes of experimentation, learning and human development. No one strategy or model is usually sufficient but a combination of two or more is more likely to be complimentary and necessary to fulfil the aims of extension.

It describes the four major strategies or models in agricultural extension as:

1. Linear ‘top-down’ transfer of technology

- Traditional model of agricultural extension based on the assumption that technologies and knowledge are developed and validated by professional research scientists, where the task of extension practitioners is to promote the adoption of these innovations by farmers to increase farm production.

- Key strengths: provides access (and translation of) scientific innovations to assist in improving farming production

- Key criticism: Farmer knowledge, skills and adaptive abilities are systematically and unjustifiably devalued in this model

- Please see Adoption Diffusion Theory for more details – provide link

2. Problem solving (one-to-one advice or information exchange)

- The trend of governments providing one-to-one advice on-farm through publicly funded extension agencies is weakening with the privatisation of advisory services (e.g. accountants, bankers, agricultural input suppliers, processors, agricultural consultants)

- Farmers are developing their own information and knowledge networks that cross the public, private and Not-for Profit sectors to solve on-farm problems. This is creating a pluralist extension system.

- Key strengths: information rich extension environment

- Key criticisms: there is a risk of small scale and low income farmers having little or no access extension knowledge and information in user-pay extension system, there is risk of the fragmentation of the Research, Development and Extension system through a deficiency in coordinating infrastructure and a lack of incentives to cooperate

- Please see Pluralistic RD&E systems theory for more details – provide link

3. Education (formal or structured)

- Farmers who participate in training events have been reported to be more likely than others to make changes in their on-farm practices (Kilpatrick, 1996)

- While there is a tendency for farmers to be reluctant to undertake formal or long-term educational courses for a number of reasons, many farmers are willing to undertake planned learning activities that are directly relevant to their farming and require relatively short blocks of time

- Farmer preferences for planned learning that are closely related to adult learning principles include: specific content relevant to current and future developments, short and modularised courses that involve project-based learning and flexible delivery formats

- Key strengths: the social interaction associated with group learning can serve as a motivating factor for engaging in learning, increased competencies to assist in achieving farming goals and the possibility of gaining credentials that could be used as another income source

- Key criticisms: there is a risk of small scale and low income farmers having little or no access extension knowledge and information in a user-pay extension system; a fragmented Research, Development and Extension system can result from pluralism because of a deficiency in coordinating infrastructure and a lack of incentives to cooperate across the private, public and Not-For-Profit sectors

- Please see Social Learning Systems theory for more details – provide link

4. Participatory ‘bottom-up’ participatory approaches – human development

- Alternative models were developed (1970s) in response to the criticism of the ‘top-down’ transfer of technology model

- New focus on experimentations, learning and action with farmers and scientists

- Approaches to farmer participation varies from farmer input into research to emphasising farming community empowerment whereby the farmers themselves drive the research, development and extension to achieve economically and environmentally sustainable farming systems

- Key strengths: recognise and value local knowledges, provide capacity building opportunities for farming communities, allows for landscape scale framing of problems, peer-to-peer networking and ownership of problem

- Key criticisms: limitations with local knowledge of complex problems, unresolved competing and conflicting conceptions of problem, limited farmer capacity to participate and lack of attention to group dynamics and self-development of group

- Please see Farmer Participatory Theory for more details – provide link

The figure below is based on the extension spectrum depicted by Campbell and Junor (1992) based on Van Beek and Coutts (1992) representation.

Figure 1. Source: Black, (2000:496)

It illustrates that as extension situations become more complex, emphasis should be given to approaches, processes and tools that empower people to engage in ongoing processes of experimentation, learning and human development. This is not to disregard the role of technological knowledge and know-how, but that complex situations need to build on and extend from a technology transfer approach to involve more complex social processes.

No one strategy or model is usually sufficient, but a combination of two or more is more likely to be complimentary and necessary to fulfil the aims of extension.

Each strategy or model has strengths and weaknesses that should be understood when developing an extension program, project or series of activities. Therefore, a conviction in a ‘participation fix’ may be just as misguided as a belief in a ‘technology fix’.

Content source and further information

Black, A.W. (2000) Extension theory and practice: a review. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 40(4) 493 – 502

Campbell A. and Junor R. (1992) Land management extension in the ‘90s: evolution or emasculation? Australia Journal of Soil and Water Conservation Vol. 5(2):16-23

Kilpatrick, S. (1996) Change, training and farm profitability. National Farmers Federation, Research Paper 10, Barton: ACT

Van Beek, P. and Coutts, J (1992) Extension in a knowledge systems framework. Queensland Department of Primary Industries Systems Study Group, Discussion Notes 2

Campbell, A., and International Institute for Environment and Development, (1994). Community first: LandCare in Australia. London: Sustainable Agricultural Programme of the International Institute for Environment and Development. p.12>http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/6056IIED.pdf