The Diffusion of Innovations theory was the leading theory in agricultural extension post World War II until the 1970s. It is still used today in agricultural extension, particularly when extension is concerned with an adoption of a particular technology (i.e. technology transfer approach to extension).

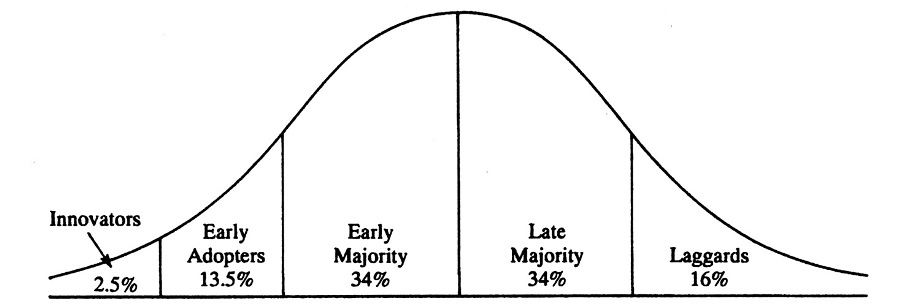

Rate of adoption is a key feature of the theory – Everett Rogers developed adopter categories to ‘measure’ innovativeness of farmers to produce a statistical model (normal distribution curve) to show the distribution of the five adopter categories over the average time of adoption, please see the diagram below.

Source: Adopter categorizations on the basis of innovativeness – Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press

Everett M. Rogers is considered a founder of the Diffusion of Innovations theory. Rogers undertook a PhD (doctoral dissertation) in 1957 analysing the diffusion of several agricultural innovations in a rural community in Iowa. Rogers was convinced that the adoption of innovations follows a universal process of social change. It originated in communications to explain how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and spreads (or diffuses, hence the name) through a specific population or social system.

Everett Rogers, 1934 – 2004 Source – Leadership Network

There are four main interacting elements of the key concept: Diffusion of Innovations – 1) an innovation, 2) communicated through certain channels, 3) over time and 4) among members of a social system.

Definitions

- Innovation: Is an idea, practice or object that is perceived as new by an individual or group [or organisation]. (Rogers, 2003:12)

- Communication: The process by which participants create and share information to one another in order to reach a mutual understanding (Rogers, 2003:18)

- Time: Time involved in the innovation-decision process, the time taken to adopt an innovation by the adopter and the adoption rate across the social system (Rogers, 2003:20)

- Social system: Are a set of interrelated social units (e.g. individuals, informal groups, organisations) that are engaged in problem solving to achieve a common goal. (Rogers, 2003:23) – it determines the boundary for a diffusion process; it can be affected by norms, and the degree to which individuals can influence one another

These four elements are present in every diffusion research study and in every diffusion program (i.e. the main elements are the variables in the diffusion process).

Rogers Adoption Categories Explained

Innovators (2.5% of social system population):

- A “venturesome” approach to change

- Quick to take up new ideas, knowledge and technologies

- Cope with uncertainty and failure

- Risk-takers

- Play an important role in introducing innovations into the system and plays a gatekeeper role in the flow of information in a social system.

Early Adopters (13.5% of social system population):

- “Respected” members of the system

- Represent opinion leaders and are more integrated into the social system than innovators

- Provide advice and information to others about innovations

- Are already aware of the need to change and so are very comfortable adopting new ideas

- Early adopters help trigger the critical mass when they adopt an innovation (i.e. considered a “stamp of approval”)

- Has a central position in the social system (communication network).

Early Majority (34% of social system population):

- “Deliberate” need to see evidence, think about and be convinced by others before being willing to adopt

- Adopt innovations before the average person

- Rarely perform leadership roles

- Serve as important links in the diffusion process as they are the connection between very early and the relatively late adopters.

Late Majority (34% of social system population):

- “Sceptical” cautious about change and have a questioning attitude to innovations

- Adopt new ideas just after the average person

- Adoption may result from peer pressure or economic necessity rather than motivation for change

- Innovation must be well supported by social norms to be desirable

- Possibly have few resources therefore most of the uncertainty of the innovation must be removed before the late majority feel comfortable with adopting innovations.

Laggards (16% of social system population):

- “Traditional” in that they are bound by tradition and are very conservative

- They are not opinion leaders and mostly considered ‘isolates’ in a social network sense (not connected strongly or to many other system members)

- The points of reference for laggards is the past

- They are very sceptical of change and are the hardest group to motivate to adopt innovations

- They take a lengthy amount of time to adopt in association with awareness of innovation

- They demonstrate resistance towards innovations and are risk averse

- They are in a vulnerable economic situation, therefore access to resources is constricted

- Blame for not adopting can be located at the individual and system level.

Rogers also listed a series of correlations that show the positive relationship between a series of social variables and the likelihood of being an innovator type. Examples of these include:

• Education

• Literacy

• Higher social status

• Large-size farms

• Commercial economic orientation

• More favourable attitude to credit

• More favourable attitude to change

• More favourable attitude to education

• Intelligence

• Social participation

• Urban contacts

• Change agent contact

• Mass media exposure

• Exposure to interpersonal channels

• More active information seeking

• Knowledge of innovations, and

• Opinion leadership.

The implication of adopting the theory is that extension professionals/practitioners need to develop different practices/messages for different ‘types’ of adopters (i.e. farmer segmentation).

There are five main characteristics of innovations that determine how an innovation will be responded to by a potential farmer/end-user:

- Relative Advantage – The degree to which an innovation is seen as better than the idea, program, or product it replaces.

- Compatibility – How consistent the innovation is with the values, experiences, and needs of the potential adopters.

- Complexity – How difficult the innovation is to understand and/or use.

- Trial ability – The extent to which the innovation can be tested or experimented with before a commitment to adopt is made.

- Observability – The extent to which the innovation provides tangible results.

Rogers proposed a set of stages in decision-making in adopting an innovation:

• Knowledge

• Persuasion

• Decision (adoption or rejection)

• Implementation

• Confirmation

Source: Conceptual model of Diffusion of Innovations- Rogers, E.M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th edition). The Free Press. New York.

Application of the Theory

The theory has been used in rural sociology/agricultural extension and also in disciplines such as anthropology, public health and general sociology.

In respect to the agricultural sector it has been widely used by extension program planners, evaluators and researchers to develop an understanding of the reasons why extension programs result in adoption or rejection of a particular new practice. It also provides a general understanding of the impact of extension programs through the extent/degree of innovation adoption.

Many governments of developing economies have used the Diffusion of Innovations theory to shape the conceptual framework and implementation design of international rural development programs.

For our article giving case studies and discussion on the use of the theory, see here

Critique of the Theory

Publicised criticisms of the theory started to appear in the 1970s in the context of international development projects (Rogers, 2003). The key criticism was that innovations were being targeted to the “Innovators” and “Early Adopters” – the more ‘progressive’ farmers, with the expectation that innovative practices would trickle down to the majority of farmers.

However, the reality was that the application of the theory was viewed as a source of inequity, dividing rural communities and not benefitting/assisting those in most need. This was particularly noticeable when the diffusion of innovations process benefited larger farmers by increasing their production but decreasing the market prices/farm gate returns received by all farmers in the region (including the non-adopters) (http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/602#.VuEUoUYutAM; Goss, 1979).

Other limitations of the theory have been described by Rogers himself: (Rogers, 2003:130-135)

- A Pro-Innovation Bias – There is the implication that an innovation should be diffused and adopted by all farmers. The act of innovating is considered positive and the act of rejecting an innovation is considered negative.

- Individual-Blame Bias – The development agency is not blamed for its lack of response to the needs of farmers. Rather, the individuals who do not adopt the innovation are blamed for their lack of response.

- Issue of Equality – The negative impacts of the theory are not considered. What are the consequences in terms of unemployment, migration of rural people and equitable distribution of incomes? Will the innovation widen or narrow socioeconomic gaps?

- Bias in Favour of Larger and Wealthier Farmers – Innovation investors tend to target the already innovative, successful and information-seeking farmers who have the capacity to resource themselves to experiment and adopt an innovation – which can lead to great productivity/profitability, consequently the social divide amongst farmers widens as a result.

Limitations of diffusion research: (Van de ban and Hawkins, 1988:119-122):

- It tends to assume innovations originate at research institutes/central agency rather than farmers themselves, other players in the RD&E system.

- It assumes adoption of innovation is always desirable (normative), it tends not to evaluate innovations from an end-user perspective.

- There is a risk of technical/research messages being lost in translation to the farmer because of the language used.

- It assumes there is enough research information available to the extension/change agent and does not tend to see knowledge as a combination of research outputs plus the farmer’s knowledge, experience and interpretation of the problem.

- There are few systematic evaluations of the adoption and diffusion model, research on model does not tend to focus on systemic change (changes to the social system), rather the focus is on discrete technical changes, changes by individuals and groups rather than institutions and societies as a political project

For a great opportunity to hear Everett Rogers speak on the Diffusion of Innovations, watch the ProBusiness Video and Schreiner Productions, Salt Lake City, Utah YouTube Video below.

Content Sources and Further Information

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press (Book)

To see an explaination of the Diffusion of Innovations, by Prof Michael Rosemann of Queensland University of Technology 101 see the YouTube Video, Published February 11th 2015

For critique – Van den Ban, A. W., & Hawkins, H. S. (1998). Agricultural Extension (2nd ed). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell Science Ltd. (Book)

Beever, G. (2018). Blog post: Diffusion of Innovations Theory: Case Studies and Discussion. extensionAUS, Extension Practice.