Umali and Schwartz developed a schema that categorises agricultural knowledge and information into an economic classification system. This system denotes the character of the knowledge and information and the degree to which farmers are prepared to pay it. The categorisation is used to inform the appropriate roles for the public and private sectors.

The contemporary agricultural extension system is facing multiple challenges: greater demand for food from a growing human population in the context of constrained food-producing capacity (labour, land resources, natural resource degradation); significant populations still rely on agriculture to support their livelihoods therefore research, development and extension and rural development programs remain important mechanisms to enable agriculture to continue to support both global food needs and farming families livelihoods.

The big question asked by this theory is what should the role of the government be in agricultural extension systems, considering extension systems are evolving towards pluralism (the public sector, private for-profit sector and the private non-profit sector) with greater emphasis on the role of the private for-profit sector.

In the past the traditional view of the “public good” character of agricultural extension services with the positive on-farm and industry scales benefits was incentive for many national and regional governments to take the lead role as funder/investor and delivery provider. However, this theory recognises that there are three major developments that have caused a rethink of the role of governments in the agricultural extension system:

- Financial crises and budget cut backs have meant the restructuring of the agricultural sector including investment in agricultural extension services.

- Poor performance of certain public extension programs has led to questioning the efficiency, quality and effectiveness of public sponsored/delivered extension programs and inspired a search for alternative approaches to providing extension services. The public extension system was also criticised for weak connectivity between farmers and the agricultural research sector.

- Agriculture’s reliance on more specialised knowledge and technologies has meant that the economic character of the extension services delivered has changed (i.e. the institutionalisation of mechanisms that permit the retailer to appropriate the returns from new innovations – examples include patents, plant breeder’s rights etc.). This has provided greater incentives for the private for-profit sector to be engaged in providing extension services as a business venture.

In Summary

The theory proposes:

“The growing commercialisation of agriculture and increased competition in domestic and international markets have further strengthened the economic incentives for farmers and other rural entrepreneurs to treat extension as another purchased input to agricultural production and marketing activities.” – Umali-Deininger, 1997:206

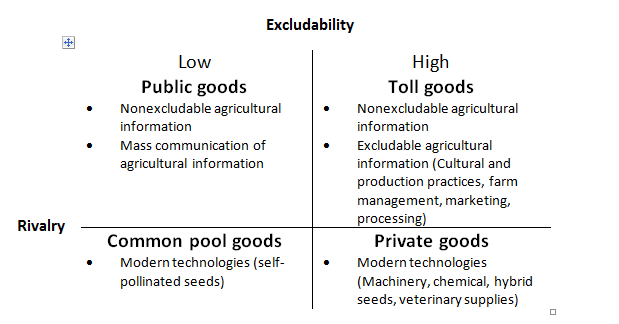

Umali and Schwartz (1994) in line with Umali-Deininger work in 1997 developed a schema that categorises agricultural knowledge and information into an economic classification system. This system denotes the character of the knowledge and information, and the degree to which farmers are prepared to pay for that knowledge and information.

The economic categorisation of agricultural knowledge and information is used to inform the appropriate roles for the public and private sectors.

Economic classification of agricultural information and technologies of the agricultural extension system – Umali-Deininger, D. (1997) The World Bank Research Observer, voll2.no. 2: 209> Extension knowledge and nformation falls within a range of public goods moving towards fully privatised goods with categories in between (toll goods and common goods)

Using economic principles of rivalry and excludability, extension knowledge and information is proposed to be able to function as a competitive commodity.

Some underlying principles:

Rivalry means that when a farmer uses or consumes a good or service, it reduces the supply of this good or service to others, making it a scarcer resource (e.g. buying a piece of equipment from the local supplier means one less is available to purchase by others).

Excludability means when a farmer pays for a product or service they benefit from the purchase solely in terms of access, use and outputs.

Private goods are any good that is both rival and excludable (e.g. modern technologies such as machinery, chemicals, hybrid seeds, self-pollinated seeds, biotechnology products, veterinary supplies). Private companies tend to be unwilling to supply goods and services with public good characteristics because they are not excludable (the benefits derived from the goods cannot be restricted to the purchaser). Farmers will not be prepared to pay for knowledge and information (e.g. soil conservation techniques, if this information is also available through mass communications for free; use of legal mechanisms provides a high degree of excludability such as patents, copy rights etc.). If the private goods and services become too expensive to individual farmers, then these goods can be accessed in a more affordable way through farmer groups/associations by collectively organising and paying for services that is, the private goods are accessed as a toll good.

Public goods are neither rival or excludable (e.g. mass communications of agricultural information by the public sector). Non-excludable knowledge and information that may start as a toll good may become a public good by the process of diffusion (i.e. word of mouth, local promotion strategies). If the knowledge and information diffuses easily then there will be little incentive for the private for-profit sector to enter this space, therefore non excludable knowledge and information is likely to remain the responsibility of the public and private not for profit agencies. In certain conditions private for profit firms will undertake supplying public goods if it translates into greater financial returns from an improved agri-food system.

Toll goods are exclusive but low rivalry; (e.g. certain plant breeds that are only accessible through a club membership). The ability to exclude those who have not paid for the service provides the incentive for private sector to be active in this space. An additional member attending an exclusive event doesn’t reduce access to the knowledge and information of other members. It tends to be specialized knowledge and information specific to location or client group, such specialization increases the exclusivity of the good by being applicable to specific conditions. The role of the public sector for toll goods and services would be to regulate pricing, setting quality service standards, establishing property rights and the conditions for competition. The non-private sector can also be involved in distributing publics goods as a toll good, such as natural resource management practices and environmentally sustainable production techniques to certain farmer groups.

Common-pool goods are high rivalry but low excludability; (e.g. self-pollinated seeds from public sponsored programs or private firms). Goods (i.e. knowledge or product) are available to everyone that is people cannot be stopped from using them, however using the goods reduces the access of the goods for others. Private firms may initially supply a private good, but if it can be supplied independently from the private firm such as self-pollinating seeds, then the private sector will be competing with the farmers in supplying seeds for crop production. Only relatively small and local firms/local agencies with low overhead costs can be expected to supply goods in this space.

Market failure can be a major implication of research, development and extension services. This can occur when a shift from a free/public good to a purchased good is that the private sector tends to service those medium to large-scale farmers that are market orientated and can afford to purchase goods and services at optimum prices. This creates the risk of marginal and small scale farmers being neglected and unable to access essential research, development and extension services. There is a role for the public and non-profit agencies to ensure the marginal and small scale farmers can access and are engaged with the RD&E system.

Funding, the responsibility for funding different types of agricultural extension knowledge and information (as per the described economic schema) will depend on the economic characteristics of the knowledge and information and the structure of the local farming sector.

However, farmers tend to be most willing to pay for goods and services that are classified as a toll good – although many countries are trending towards a pluralistic RD&E system which will require organising around four functionalities:

- Source of funding

- Client targeting

- Cost recovery, and

- Delivery channels among governments, NGOs, farmer collectives, private firms and individual consultants

However, it remains unresolved what roles and degree of influence the public and private sectors should play in each nation’s RD&E system (e.g. countries in Latin America are designing RD&E around a demand-driven system, including farmer co-financing of extension services, decentralization of financing and planning to municipalities and use of farmer groups). This is considered part of a transition phase in developing a market-based fee-for-service extension system, or it might involve public-private partnerships with a government subcontracting private consulting firms to delivery publicly funded extension programs.

Content sources and further information

Umali-Deninger, D and Schwartz, L. A. (1994). Public and Private Agricultural Extension, Beyond Traditional Frontiers. Washington DC: World Bank. pp. 205-224